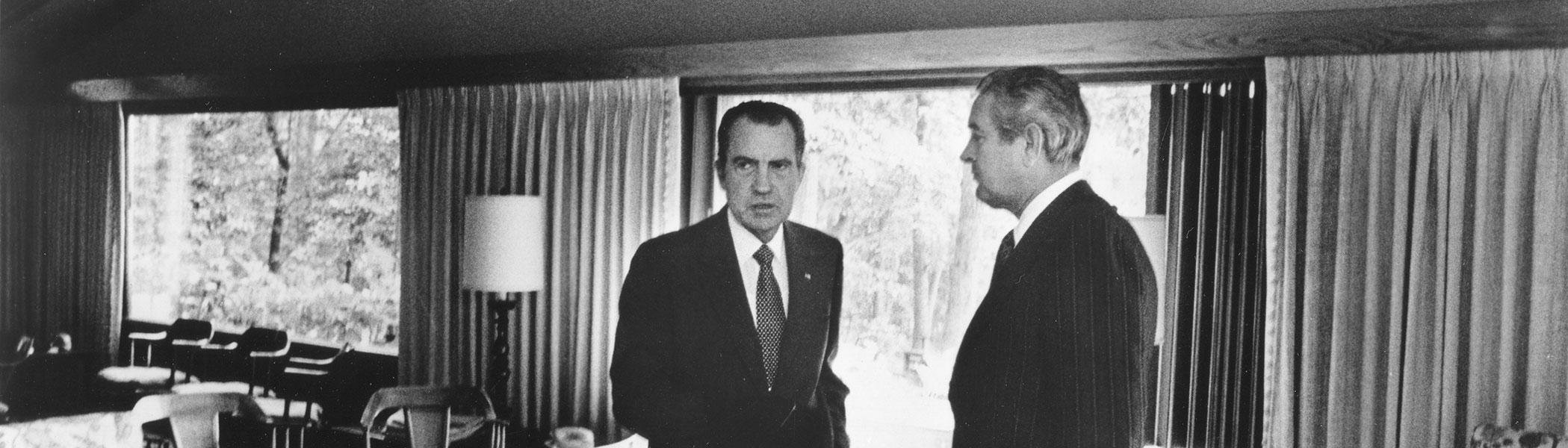

Fifty years ago, the world changed. On August 15, 1971, US President Richard Nixon slammed shut the “gold window,” suspending dollar convertibility. Although it was not Nixon’s intention, this act effectively marked the end of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. But, in truth, with the rise of private cross-border capital flows, a system based on fixed exchange rates for the major currencies was no longer viable and Nixon’s decision—decried at the time as an abrogation of America’s international responsibilities—paved the way for the modern international monetary system.

The collapse of Bretton Woods prompted a fundamental rethink about what would give stability to the international monetary system.

The Bretton Woods era

When the Bretton Woods system was established in 1944, the prevailing narrative was that competitive devaluations, exchange restrictions, and trade barriers had worsened, if not caused, the Great Depression. Accordingly, IMF member countries would only be allowed to alter their exchange rate parity in cases of “fundamental disequilibrium”—the thinking being that stability of individual exchange rates (ruling out competitive devaluations) would result in stability of the overall system. Importantly, however, it was only the member country that could propose a change in the parity—the IMF’s sole power was to approve or not approve the proposed change.

The system incorporated elements from the previous “gold standard” system, but now, instead of currencies being tied directly to gold, countries fixed their exchange rates relative to the US dollar. In turn, the United States promised to provide gold, on demand, in exchange for dollars accruing in foreign central banks at the official price of $35 per ounce. All currencies pegged to the dollar thereby had a fixed value in terms of gold.

In an extraordinary surrender of national sovereignty for the common good, member governments undertook to maintain a fixed parity for their exchange rate against the US dollar unless they faced a “fundamental disequilibrium” in their balance of payments. The IMF would lend reserves (usually dollars) to enable central banks to maintain the parity in the face of temporary shocks to their balance of payments without “resorting to measures destructive of national or international prosperity.”

The system worked reasonably well for over two decades. However, cracks emerged. Governments of deficit countries with overvalued currencies often delayed necessary devaluations for fear of the political repercussions. Meanwhile, surplus countries, which were enjoying a trade competitiveness advantage, had no incentive to revalue their currencies.

Experience during the 1960s showed that this artificial stability of individual exchange rates could delay necessary adjustment, ultimately ending in traumatic balance-of-payments crises that resulted in instability of the system, especially if one of the major economies (for instance, the United Kingdom) was involved. The rise of private capital flows meant that any whiff of a possible devaluation would send billions of dollars out of a deficit country—thus precipitating the devaluation—and into surplus countries that would struggle to contain the inflationary consequences of the capital inflows.

In the early 1970s, the United States suffered such a balance-of-payments crisis, mainly due to its lax domestic monetary and fiscal policies as it sought to finance the costs of the Vietnam War and the “Great Society” programs, together with the reluctance of the major surplus countries (notably Germany and Japan) to revalue their currencies. As the United States hemorrhaged gold reserves, Nixon decided to close the gold window. Though intended as a ploy to force surplus countries to revalue their currencies, since the dollar was the lynch pin of the system, Nixon’s action effectively brought down the system.

New system, new thinking

The collapse of Bretton Woods (and its short-lived successor, the Smithsonian Agreement) prompted a fundamental rethink about what would give stability to the international monetary system.

In devising the Bretton Woods system, the presumption had been that fixing individual currencies against gold or the dollar would make the system stable. However, in the aftermath American officials argued that simply fixing the exchange rate would bring rigidity, not stability. Attempts to maintain the peg (including through exchange restrictions or capital controls) when the exchange rate grew out of line with domestic policies only resulted in costly—and ultimately futile—delays in external adjustment.

The new thinking was the stability of the system would come less from the stability of individual exchange rates per se, and more from domestic policies being directed toward domestic stability (orderly growth with low inflation), which would result in stable but not excessively rigid exchange rates, thus allowing for timely external adjustment, and hence contributing to the stability of the overall international monetary system. While countries were no longer required to declare and maintain a fixed parity for their exchange rate, to prevent possible competitive devaluations/depreciations or other currency manipulation, the IMF was charged with exercising “firm surveillance” over its members’ exchange rate policies.

Subsequent experience (especially the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis) showed that even such domestic stability may not suffice for stability of the system when it comes to systemically important countries. More recently, countries now regularly discuss with the IMF the external spillovers from their domestic policies. And though they would never be required to alter those policies provided they are promoting their own domestic stability, they may be encouraged to consider alternative policies if those better promote stability of the system as well.

What the future may hold

The collapse of the system of fixed exchange rates shook the world in 1971. But monetary systems exist to serve the needs of mankind, and as our societies evolve, so too must our societal systems. The world in 1971 was not what it was in 1944—just as our world today bears only some resemblance to the realities of 1971. Today, fundamental transformations are accelerating the development, deployment, and adoption of digital money. Could a digital transformation of the international monetary system soon be underway? Regardless of how the system evolves, the bedrock principle that its stability will depend on international monetary cooperation, will remain.